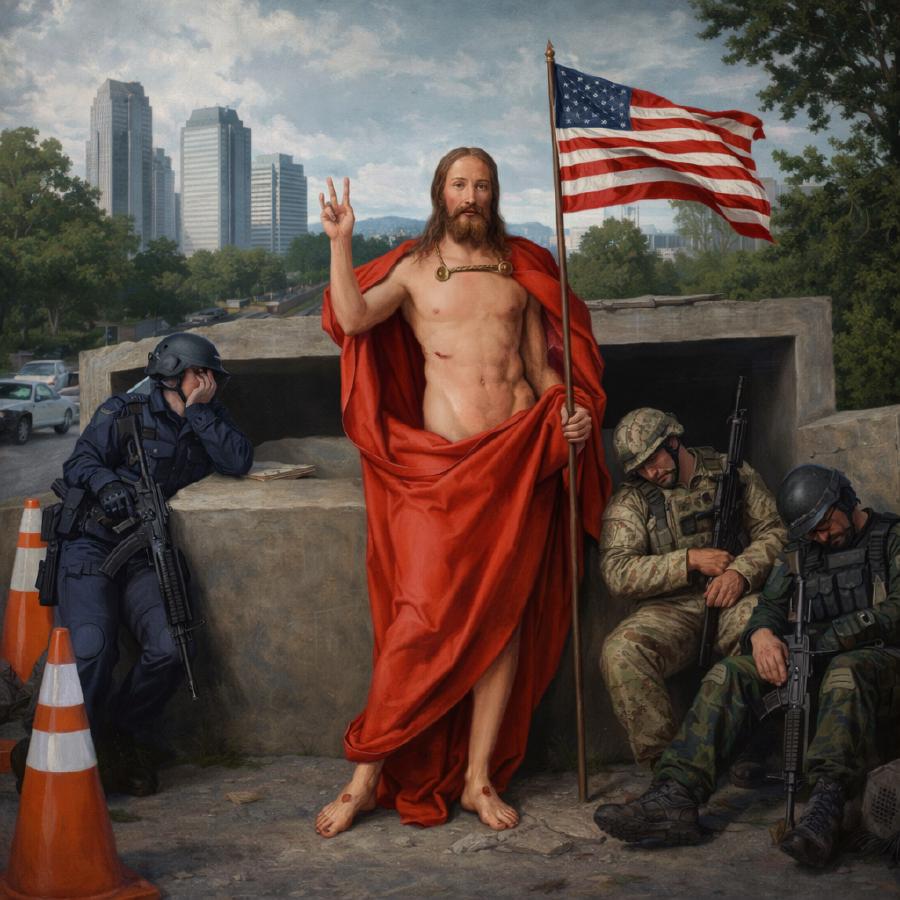

There is something immediately compelling about the first painting. Even for someone who has never studied art history, it possesses that quiet authority by which authentic works of art announce themselves. The composition is balanced. The colors are rich without being gaudy. The figures—though stylized—are presented with intention and meaning. The scene holds together. It feels as though it has earned its place in the long memory of the Church.

Many Christians would recognize it instinctively as the kind of image that belongs in a church: not merely decorative, but devotional—something that can bear contemplation. It has inspired many. It has endured. It has done what sacred art is meant to do: not simply illustrate an event, but open the heart to the reality of it. The Resurrection is not presented as a distant myth, but as a moment of victory that still addresses the viewer. Christ’s gesture of blessing, the wounds in his hands and feet, the banner of triumph, the helplessness of the guards—all of it draws the viewer into the strange and holy reversal at the heart of the gospel: the dead man lives; the one who was slain reigns.

And then, once the eye settles, one detail begins to work on the mind: the soldiers.

They do not look like Roman soldiers from the first century. They look like soldiers from the painter’s own world. Their armor and weapons belong to a later time. The scene contains a deliberate anachronism, and it is precisely this “mistake” that makes the painting theologically intelligent. The artist is not careless. He is proclaiming something.

We live in an era that often equates historical accuracy with truthfulness. We tend to assume that to depict the Resurrection properly, one must depict it as it happened, as though the goal were an archaeological reconstruction. But sacred art is not documentary photography. Its purpose is not merely to inform, but to reveal. It is meant to speak of realities that are not imprisoned in one moment. In that sense, the anachronism in the first painting is not a flaw. It is essential. It is one of the ways the artist confesses the Incarnation.

God became man. That phrase is so familiar that it can slide past the mind without sticking. Yet it is one of the most staggering claims a human being can make. The eternal Son does not merely appear to be human; he does not merely take a human disguise; he truly becomes man. He takes on the whole of the human condition. He enters history—real time, real flesh, real blood, real suffering—and he makes it his own.

And because he enters history, he does not enter only a single century in the abstract. He enters humanity. He enters what it means to be one of us.

That is why the anachronisms matter. The painter is saying, in his own visual language: Christ did not come only for “them,” back then. Christ comes for us. Christ is not only “in the time of Christ.” He is not contained by the first century as though the Incarnation were a brief divine experiment. If God has truly taken human nature, then the humanity he has taken is the humanity we share. The human condition is one, though it unfolds across countless cultures, languages, and eras.

In the first painting, Christ stands bodily present in a landscape that resembles the painter’s world. He rises before soldiers who look like men the painter might have passed on a street or seen at a city gate. That is not a careless blending of times. It is an incarnational claim: Jesus is as present bodily in the age of the artist as he was in the age of Pilate and Caesar. The Resurrection is not an event that belongs only to those who lived within a few miles of Jerusalem two thousand years ago. It is an event that addresses every age because it reveals what God has done with human nature itself.

There is also something worth noticing in how naturally the first image achieves this. We do not experience the anachronism as offensive. At most we experience it as quaint. We may even find it charming. It is easy to accept that medieval or Renaissance soldiers might appear at the tomb. We can make room for the painter’s “translation” of the gospel story into his own moment. We can accept that the sacred event speaks into his time.

But then we turn to the second image—the contemporary version—and the response changes.

It may be difficult even to name what we feel at first. It is not exactly disbelief. We recognize the symbolic structure: Christ stands at the center, bearing the banner of triumph; soldiers slump around him, overwhelmed and powerless. Yet the image strikes many viewers as odd, even unsettling. For some, it may feel irreverent or offensive. Something in us resists seeing Christ in such a setting. The modern gear, the urban background, the traffic cones, the rifles—these details jolt us out of the devotional posture we easily assume before the first painting.

It is certainly AI-generated, and one might be tempted to make that the decisive point: the first painting is art; the second is an artificial imitation. Yet that is not the heart of what troubles us. Even if the second image were painted by a master, many would still feel discomfort. The problem is not primarily the medium. The problem is recognition.

We struggle to see Jesus in today’s world.

That line is not an accusation as much as a confession. It reveals something about the imagination of faith in our time. We are often willing to grant that Christ can be present to medieval Europe on a panel painting. But we hesitate when Christ is placed—visibly, bodily—into our own contemporary landscapes. We prefer the safety of distance. We find it easier to contemplate Christ when he is framed by “religious time,” by the aesthetic language of the past. But when the image moves too close, when it presses the Resurrection up against the textures of modern life, we begin to protest.

Why?

Part of it is aesthetic. Contemporary scenes are cluttered. Our world is visually chaotic. There is less symbolic clarity in the modern environment. It is harder to compose a city street into a coherent icon.

Part of it is political. A modern setting brings associations: nationalism, militarism, conflicts that are still raw. A flag in the first painting feels like a symbol. A flag in the second painting feels like a statement. And perhaps, without even realizing it, we begin to treat the Resurrection as something that ought to remain above controversy. But if the Resurrection is real, it is never merely “above” history. It judges history and redeems it. It confronts human power in every age.

Part of it is spiritual. We have been trained—subtly, over centuries—to imagine holiness as belonging to a world set apart from ordinary life. We often treat faith as an “addition” to modern existence, rather than its foundation. We attend mass; we pray; we read scripture; but we are tempted to keep the claims of Christ neatly inside the bounds of “religion” as a sphere distinct from the rest of reality. When the Resurrection appears in the middle of our world—amid traffic, concrete, modern weapons—we feel the boundaries blur, and that makes us uncomfortable.

Yet this discomfort exposes something serious: if we cannot see Christ in our own age, then we have not fully received the Incarnation.

Christ is still among us. He is present to us in his body.

That is not pious metaphor. Christianity is not a religion of nostalgic remembrance. The Resurrection is not merely the story of a man who lived long ago. Christ died and rose for us, and he remains present to us: in the Church, in the sacraments, in the poor, in the proclamation of the word, and above all in the Eucharist, where his Body is not remembered but given.

To say that Christ is present to us in his body is to say something cosmic. The humanity he assumed is not a temporary costume. It is now inseparable from the divine life. Human nature has been taken into God. That means that the story of the world has changed, not only morally but ontologically—at the level of what reality now is. The Resurrection is not simply a happy ending to a tragedy. It is the beginning of a new creation.

And if that is true, then the Incarnation cannot be confined to the past. It cannot be treated as the sacred exception to “real life.” It is the revelation that God has entered “real life” as such and has made it the place of salvation.

The two images, then, do more than contrast medieval art and contemporary AI imagery. They expose a tension in the modern Christian imagination. The first image feels beautiful and suitable for a church. The second image feels strange. But why should that be? If Christ is Lord of all history, why should he appear at home in the fifteenth century and out of place in the twenty-first?

Perhaps it is because we quietly believe—without saying it out loud—that our moment is too secular for Christ. We might not state it so bluntly, but we often act as though holiness belongs to the “then” of scripture and tradition, or to the “there” of explicitly religious settings, but not to the “here” of contemporary life in all its complexity.

This is the problem the second image forces us to face. It looks odd because it insists that the Resurrection is not merely a past event but a present claim. It insists that Christ is not only a figure of religious art, but the living Lord who confronts every culture and every century.

And this leads to another uncomfortable truth: we are tempted to treat our moment in history as special.

Modern people often imagine themselves as standing at the peak of an upward climb. We have advanced technologically. We have developed systems of governance and medicine and communication that our ancestors could not have imagined. We can place satellites in orbit and map the human genome. We can build machines that generate images at the click of a button. All of this can create the feeling that we live in a uniquely important time—that we are somehow the culmination of human history.

But from the standpoint of the gospel, that is not how history works.

Today—this moment—is not, in the grand scheme of things, special. It is one more moment. We are not better than our ancestors, and we are not worse. We have different temptations, different forms of anxiety, different conveniences and dangers, but we remain the same humanity: fragile, longing, capable of beauty and cruelty, made for communion, often choosing isolation. Our technology, our progress, our systems of governance—these are continuations of the long arc of human history, but still fundamentally human and natural. They are not the arrival of a new kind of creature.

We remain human beings, and human beings still need the same salvation.

The Resurrection, then, is not an archaic story that we keep for sentimental reasons. It is the truth about what God has done for humanity as such. It is the proclamation that death does not have the last word. It is the announcement that the world’s deepest reality is not violence or decay or entropy, but the self-giving love of God that raises the dead.

To say this is to say that Christ confronts every age. He confronts the age of swords and armor, and he confronts the age of rifles and surveillance. He confronts the age of empire and the age of democracy. He confronts the age of parchment and the age of algorithms. None of these ages are neutral. Each has its idols. Each has its fears. Each has its forms of injustice and its possibilities for virtue. But in every age, the Lord of history stands with his wounds and his blessing, not as a relic, but as the living judge and savior.

This is why a greater appreciation of the Incarnation is not a luxury for theologians; it is a necessity for faith.

Without the Incarnation, Christianity becomes either a moral system or a mythic story. If Christ did not truly take our nature, then the sacraments become symbolic gestures rather than divine actions. The Church becomes a human institution rather than the Body of Christ. Salvation becomes self-improvement rather than the transformation of the world.

But if the Incarnation is true—if God has become man—then the whole of reality is charged with new meaning. Matter matters. Time matters. Bodies matter. History matters. Human suffering matters—not because it is romantic or noble, but because God has chosen to meet humanity precisely there.

The first painting, with its anachronistic soldiers, quietly teaches this. It translates the Resurrection into the painter’s moment, proclaiming that Christ is not distant from “now.” The second painting, by pressing the translation into our own age, reveals how far we may have drifted from that conviction. We may say the Creed. We may affirm that Christ is risen. But the modern imagination often struggles to picture the Resurrection as something that addresses this world—our world—as directly as it addressed the world of our ancestors.

Yet the gospel is uncompromising: Christ is risen now, and therefore the world is not what it appears to be. The powers that seem unshakable—political power, military power, economic power, cultural power—are not ultimate. The guards at the tomb represent the world’s attempt to keep death secure, to make the grave the final boundary. They are the image of human authority trying to police the edges of reality. And in every age, God steps over those boundaries.

This is the cosmic dimension of salvation. Christ does not rise merely to prove a point. He rises to begin a new creation. He rises as the firstborn of the dead, the first fruits, the pledge that what has happened to him will happen to the whole world. In him, the future has already entered the present. The Resurrection is not simply about Jesus; it is about what humanity is meant to become.

If this is true, then the Christian task is not to retreat into nostalgia. It is not to preserve the faith as a museum piece. It is to rediscover the Incarnation in such a way that we can recognize Christ in the middle of contemporary life, not as a decorative overlay but as the world’s true Lord.

That rediscovery is not primarily an artistic project, though art can help. It is a spiritual conversion. It requires that we stop imagining holiness as belonging only to the past or only to explicitly sacred spaces. It requires that we learn to see the world as the place where God has acted and continues to act.

And this is where the discomfort of the second image can become a gift.

If we find it odd to place Christ amid modern soldiers and concrete, perhaps the image is exposing the places where our faith remains compartmentalized. Perhaps it is revealing how readily we treat modern life as though it were “outside” the reach of salvation. Perhaps it is showing that we have not yet learned to contemplate the Resurrection as something that judges and redeems not only medieval battlefields, but modern ones too; not only the anxieties of peasants and kings, but the anxieties of modern people surrounded by information and noise.

Christ is still among us. He is present to us in his body. He died and rose for us. That means he has something to say to this moment. Not because this moment is uniquely important, but because this moment is part of the same human story that he has entered and redeemed.

We are tempted to think that our age is too complex for the old faith, that ancient language cannot speak to modern systems. But the Incarnation makes a different claim: God has entered the human story at its root. He has taken human nature itself. He is not intimidated by complexity. He is not rendered irrelevant by technology. He is not confined by cultural change. The Resurrection is not fragile. It is the most stable reality there is.

What we need, then, is not a new Christ for a new age. We need the old Christ, the true Christ, recognized anew. We need a deeper conviction that the one who rose from the tomb is the Lord of the present, not only of the past. We need to recover the audacity of the Church’s confession: that the carpenter from Nazareth is the meaning of history, and that his risen body is the beginning of the world’s transformation.

Only by rediscovering the Incarnation can we truly rediscover our faith. Only by recovering its cosmic scope can we escape the narrowness that turns Christianity into one hobby among many. Only by learning to see Christ as truly present—here, now, in the concrete and confusion of modern life—can we know the freedom and salvation he offers.

The first painting consoles us with beauty and tradition, and it teaches us incarnational truth through its anachronism. The second painting unsettles us, and in doing so it asks a pointed question: if Christ can be depicted as present in the artist’s age, why do we resist seeing him in ours?

The answer to that question is not a matter of aesthetics. It is a matter of faith.

And the invitation is clear: to let the Resurrection move from being a cherished image of the past to being the living center of the present; to let the Incarnation stretch our imagination until we can confess not only that Christ was among us, but that Christ is among us—and that, therefore, no age is abandoned, no moment is beyond redemption, and no corner of human history is outside the reach of the risen Lord.